FIRST STEPS IN MOUNTAINEERING

Two weeks in the Pacific Northwest with the American Alpine Institute’s AMTL 1 series: learning the basics of leading a rope team up glaciers, crevasse rescue, and multi-pitch alpine routes

A little over a year ago I decided to pursue backpacking and train myself for the outdoors in a big way. I came to that decision while hiking out of the Grand Canyon: unprepared in my denim jeans and canvas rucksack, frighteningly low on water, and alone. I needed to get better at this if I wanted to spend more time in the backcountry. A backpacking trip to Patagonia showed me that if I pushed myself a little harder, I could place myself in remote places and have longer moments to myself on the trail. There was something more I needed though. It wasn't enough to look up at the mountains surrounding me. While hiking, I'd daydream of making my way up to the top and imagine the view looking down. The only problem was that I had no idea what it took to get up there.

When I returned home, I threw myself into researching alpine-style mountaineering, and a whole world of possibilities emerged. There were a lot more technical skills needed to travel over glaciers, climb exposed sections of rocky terrain, and lead a rope team. The risk of accidents was far higher, and it wasn't as straightforward as hiking up a mountain. Rather than register for a guided summit attempt of any single mountain, I opted to take a longer course that would teach me to be more independent. In mid-July, I packed my bags and set off for Bellingham, Washington where I would spend two weeks with American Alpine Institute (AAI).

LEARNING THE ROPES

I slept in my hotel room for only five hours before waking up and bringing my gear to AAI's office. There was a tarp on their lawn and we were asked to make a spread of all our food, equipment, and clothing for the guides to take a quick inspection. For a lot of us, buying ice axes and mountaineering boots were new purchases, so we curiously looked at the items around us. All of it cost me quite a lot of money, so I was hoping I did my shopping correctly. I was also hoping I would actually enjoy mountaineering. There was of course a greater than zero chance that I could return and sell all of my specialized gear on craigslist if this trip went poorly.

The guy next to me, Luke, had a 10b tent; I offered to share my tent with him, which was half the weight of his. He was a US Marine based out of the Republic of Georgia in Eastern Europe. Through other students, I'd later learn he was a lawyer, dive instructor, and the founder of a backcountry ski guiding company (Caucasus Nomad).

It seemed nearly all of the eight students in the course were more experienced in the outdoors than myself, which I was very happy with. I preferred to be with a group I could learn from.

We spent the first day on some easy single pitch top-roping on Mt. Erie. The goal was to introduce anyone new to climbing the knots and hitches that we'd be working with, as well as how to belay a climber. Most of this was a refresher for me, so I spent more time getting to know the others in the class. I was most excited to see students who had never climbed before coming back down with a huge grin on their face, saying that they were most nervous about rock climbing and now believed they loved it.

We camped nearby at Deception Pass State Park, which would have been pleasant if there wasn't a naval air station four miles away. There was a constant whirring of jet engines above, so much so that it was comical. Fortunately, I had sleeping pills, earplugs, and needed to catch up on sleep from my flight.

APPROACH TO MT. BAKER

I woke up at 6:30am so I could have a leisurely start, and to avoid the wait for a hot shower at the campsite. Despite my early wakeup, I was the last one to pack my bag and held up the group.

Our objective was to spend the next five days on Mt. Baker. One of the guides, Will Nunez, had given a demonstration on the most efficient way to fit whatever we would need into our packs, but I was having a lot of trouble. Eventually, I gave up and he packed my entire bag for me, all while pointing out items that I wouldn't have the luxury of bringing along with me. I was surprised, but I'd later learn that I could have done the trip with even less gear.

When we got to the trailhead, I felt wobbly and uncomfortable with my heavy pack. The first few miles, as is common at the start of every hike, filled my mind with doubts: fears of cramping in my legs, worry about whether I'd last til the next water break, and why I even bothered doing this. After a few hours, my perspective flipped and I was daydreaming of experiencing whiteout conditions, kicking steps into the snow on summit day, and descending steep faces. I thought about how many gaps remained in my calendar and where I could go next with what remained in my bank account. I also knew I'd double down on my training as soon as I returned home.

I was so motivated that I felt disappointed to reach our campsite. I had it in me to keep going and wanted to take advantage of that. Luke turned out to be a great tent-mate from the start. I had only a fraction of his experience camping and having someone else to share the duties with meant we were set up in no time.

Alejandra, the other guide on our course, explained to us how we would position our bodies to poop into our "Wag Bags," which were plastic double-bags that we would use to carry out our waste. I wasn't anticipating this part, although I should have since I'm familiar with Leave No Trace principles. I only packed two wag bags so my plan was to hold it in for as long as possible (or be forced to re-use one of them).

After dinner, several of us stepped towards the sunset to get a better view of the mountains to the west of us. We joked that we would try to sneak our bags of poop into each other's packs so we wouldn't have to carry it ourselves.

MOUNTAIN SKILLS

I whacked Luke in the face in the morning when I got up, forgetting that I was sharing my tent space with someone else. The inside of our tent was dripping wet from the nighttime condensation from both of us breathing. We planned to just keep the entire tent door wide open for better ventilation next time.

On the agenda for today would be learning how to move efficiently on snow and ice. For practice, we would go run through a few techniques on how to walk up and down depending on the slope and firmness of the snow. In addition to our feet, we needed to learn how to incorporate our ice axes into our movements. The most entertaining part of the day was practicing self-arrest drills, where we would simulate sliding down a slope and jabbing the pick of our axe into the snow to slow down and eventually help stop the fall before it got out of control. We ended the lesson learning about using the rope to create a pulley system for a crevasse rescue, as well as learning how to perform a self-rescue with a prusik knot.

I took some advice from the others and put myself in a secluded spot with a view of the mountains to have my first poop in the outdoors. When I returned with my wag bag, a few of the students were impressed by the size of my package; someone even wanted to hold it to feel how heavy it was, assuming I hadn't squeezed all the air out before sealing it.

ONTO THE GLACIER

The next morning, I got a chance to meet Reinhard, a German man in his 70s who camped near us with his son. His plan was to leave the campsite and make an attempt for the summit at 3am. Unfortunately, he had heart palpitations when he woke up and decided to call it off. This was supposed to have been his last trip to the mountains to cap off a mountaineering career that spanned over 50 years.

Our destination today would be Ice Dome, a higher camp that was on the glacier, which meant we would be roping in together at a certain point. Before we broke camp, we made a decision to bury our wag bags in the snow and come back for them later. Even though it was all bagged, it was still possible to smell it so we needed a hole six feet deep.

Our visibility was limited to about 300ft at most for most of the hike because of the fog. As usual, I was dreading the hike and then finally warmed up to the trail after an hour. When we reached the foot of the glacier, we broke up into rope teams and Alejandra led a lesson on glaciology and how to navigate the more dangerous parts. We needed to know how to identify rockfall hazards, icefall from seracs, crevasse zones, weak snow bridges, and how to find a camp spot away from an avalanche path.

The reason to rope in as a team on a glacier is to increase the chance of rescue for a fallen teammate. Although the danger of everyone falling increases, the rest of the team could arrest the fall of whoever is sliding down the glacier. We were taught how to keep a safe amount of slack in the rope to avoid tugging the person behind you and to reduce the risk that you would trip over the rope if there was too much slack. Because of the careful pacing needed to manage the rope length ahead and behind you, a team is only as fast as their slowest member.

Before we could unrope at the campsite, we needed to carefully probe the area with ice axes to ensure we were on solid snow. We then spent nearly an hour work-hardening (i.e., stomping around) areas we planned to pitch a tent on, and burying stakes to prevent our tents from flying off the mountain in a strong wind. I found another reason to feel lucky that Luke was my tent-mate. He dug a trench right outside our tent that we could use to comfortably sit down in and use as a kitchen area. We ran out of water, and were told to use the melt the snow while it was soft from the afternoon sun. To the surprise of most of us, we found small centimeter-long ice worms floating around in our bottles. We fished these out with our sporks, although ingesting them wouldn't cause problems I was told.

Once we were all settled in, Alejandra began a lesson of her own. She put on some salsa and bachata music and we started a dance party that lasted well into the early evening.

INTO A CREVASSE

Although we had learned the basic concept and system of crevasse rescue, we needed to simulate the real thing with a crevasse. I was most looking forward to today, since it meant I could experience jumping off of an edge and hanging inside the glacier.

Despite only dangling 20ft from the edge, I couldn't hear the team above conducting the rescue. The walls of the crevasse ate up any noise that the rest of the team or I made. There would be random jerks of the rope that would drop me a few more inches, which was a result of the weighted rope cutting into the lip of the crevasse.

It had been the longest lesson of the day, and maybe the most important. Our plan for the following day would be to make it to the summit and then return to the van in a single push. I prepared my pack with the essentials I'd need (layers to change in and out of, and just enough food). I went to bed early that day, a little bummed out that I would miss the sunset.

MT. BAKER SUMMIT PUSH

We had our alpine start by waking up at 2am. It was dark but the moon provided enough light to see most of the campsite. We all noted that it was unusually warm, which was a great sign for us. At 4am we got into our rope teams and began the long slog up the mountain. For a few hours, 90% of my view was focused on the 3 feet of rope in front of me illuminated by my headlamp as I slowed or sped up to manage the slack. We'd be using crampons for the first time as a team, since the snow would be firm enough. The guides taught us that if the snow was too soft, crampons were more dangerous than helpful, since the snow could "ball up" under the spikes and any step could send us sliding down rather than keep us in place.

When the female members of our rope team needed to stop for a bathroom break (which would need to be done with a harness still around their waists), we were told to look the other way. It was somewhat amusing because of how exposed the mountain is, and that we were all in view of any other rope team ascending that morning. After a few breaks, we declared the name of our rope team be Team PeeParty.

It wasn't a difficult hike for me because of the training I had put in, but at about 10,000ft I began to feel nauseated. I remembered hearing about this feeling in a few podcast episodes and several minutes of 'pressure breathing' got me back to feeling comfortable again. It was also at this altitude that we approached the crater, and the smell of sulfur dominated the air.

We got to the summit at about 10AM and celebrated for about a half hour. The festivities included a dance party, multiple group photos, hugs, and high-fives.

The most unpleasant part of the entire course was the descent. I was dreading this section and had good reason to. I was probably the slowest and most careful with each step. Given that we were all roped in, I often felt the tug of Sarah ahead of me and I would try and catch up by making a few hasty steps. I was trying to ignore the tight knee pain and the sharp muscle pulls on my hip and keep the pace for the next few hours, especially while we were crossing the steep rockfall zone under the crater wall.

All of this led me to the conclusion that I needed to learn how to ski and get into ski mountaineering.

We made it back to our camp at Ice Dome and were given an hour to break our tent. At this point the snow was soft enough that we were better off without crampons.

Even though we were no longer roped in after leaving the glaciated section of the mountain, I was still nervous on the descent. My pack was holding my wag bag and I didn't want to risk having it burst with a sudden fall or jerky motion.

We returned to our first campsite and quickly dug up the wag bags we had buried in the snow. Fortunately, the marmots roaming the area hadn't discovered our cache, sparing us of having to deal with a mess. We hiked for what felt like an eternity and stopped briefly to cool down in a creek. We learned that someone in the group hadn't pooped in five days and was at this point holding it in til we made it to the car. The next few hours were filled with a mix of silence broken by occasional poop stories from our past.

As soon as we got to the car, our first destination was a burger shop to stuff our faces with grease and beer. I wasn't the only one who hadn't eaten much on the hike today, so several of us were buzzed fairly quickly. We got to a campsite at midnight and I didn't bother putting up a tent and instead slept right on my sleeping pad. I made the mistake of leaving my sleeping bag buried somewhere in the van, so I resorted to curling up and using my down jacket as a blanket.

ANCHORS AND RAPPELLS

There was a hot shower available at our campsite, but I opted to go for a swim in the lake instead to wash off the smell of five days on a mountain. The truth was that I didn't have any quarters to operate the showers, and it helped that the lake was warm. I did notice that a blister on my ankle from my boot had turned into an infection over the last few days. My ankle was swollen and awkward to stretch. I covered it up with duct tape earlier to prevent it from rubbing further, but at that point I needed to air it out.

We made a much-needed stop at a laundromat, and since we finally had service, we all stuck to our phones to reconnect with friends and family for an hour.

The lesson today was fairly straightforward. We would be learning what good gear placements would look like for rock climbing. Gear placements are intended to provide protection to a climber in case of a fall. Basically, you would insert a nut (small chunk of metal) or a cam (spring loaded devices) into a crack and attach a carabiner and sling to it. If your rope is running through the carabiner, the protection you placed should hold your fall from turning into a more dangerous drop (assuming you placed it correctly).

FIRST ALPINE MULTI-PITCH ROUTE

The short lesson yesterday served as a rest day, as well as preparation for the following two days. We would pair up with a student and a new guide in an attempt to reach the summit of a rock route that would involve multiple pitches, meaning it would be multiple rope lengths long.

I was paired with Luke, who I communicated well with. He ended up being quite supportive while I did my first multi-pitch climb. Our new guide was Sam, who was quiet at first and had more of a show-first, explain later style of teaching that Luke and I enjoyed quite a bit.

Our objective of the day was the Spontaneity Arête route on Le Petit Cheval, graded at a 5.7. I made a poor first impression by forgetting my helmet in the other van. Fortunately, the van was only a few minutes behind us and we waved it down.

The route was new to Sam, which was great for both Luke and me. We would learn more about navigating if Sam had to refer more to his map, and it also felt more like an adventure.

The entire route was fairly easy for me and I moved naturally through it. Sam asked me what my goals were for taking this course. I told him that I had a plan to combine alpine mountaineering with sailing and bike touring on a few trips in the next few years with some friends. Our first trip of this sort would be crossing New Zealand's two big islands in one direction on a chartered sailboat, and then returning over land on bike with a few mountains and rock routes to climb along the way.

We reached the top and had a brief lunch, with Sam pointing out which routes on the rock formations around us still hadn't yet been climbed. We set up a rappel off the summit and made our way down. I was last to descend, and saw two guys making their way to the summit. They yelled that they had some gear of ours that we left behind so I waited a bit for them. When they showed up, I told them it was my first multi-pitch and they told me to be careful and that two people had just died last week rappelling off of this summit.

The descent was an unpleasant experience for all of us. We made a few rappels and did some down-climbing, but the majority of it was hiking down a steep gully with loose sand and rock slipping underneath our feet. The quiet concentration of hiking down was broken every other minute by one of us yelling "rock!" as another piece careened down the slope. We tried to stay close to each other, so that if a rock were to fall it wouldn't have enough momentum to do real damage before striking the person below.

Our team returned to the campsite much earlier than everyone else, and I was bored after taking a 5 second bath in the cold creek nearby. I suggested that the three of us go to the nearby town of Winthrop for victory beers and dinner. I reasoned that the others probably were doing the same. The truth was that I wasn't looking forward to another night of freeze-dried meals.

SOUTH EARLY WINTERS SPIRE

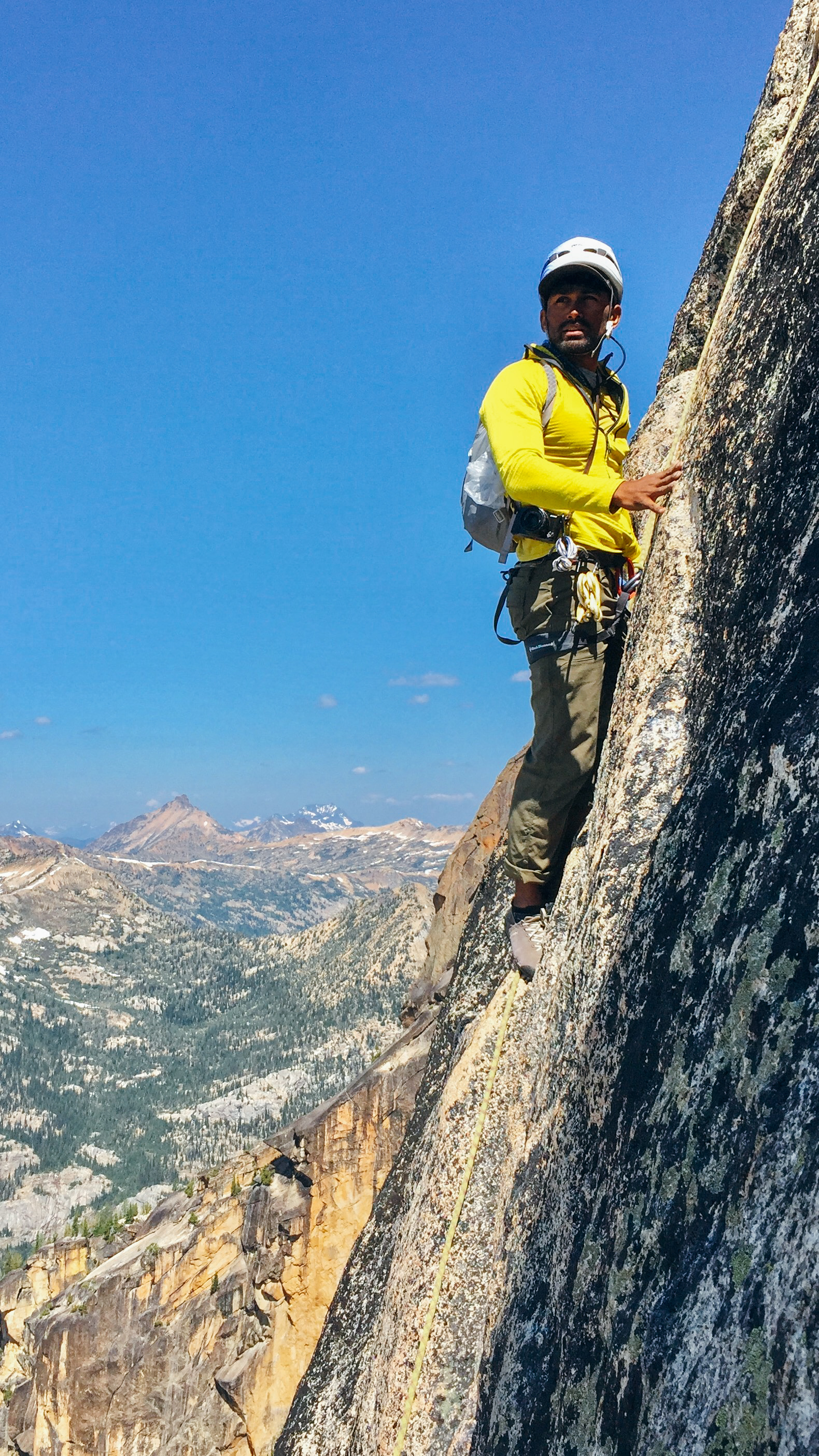

Luke had mentioned to Sam that he thought we could do a harder route that had more exposure. Sam suggested the Southwest Rib route on the South Early Winters Spire. It was one of the peaks we had a great view of from our climb yesterday. Fortunately, the approach was a lot easier and it was far more appealing to be walking through an alpine meadow.

Two other student-guide teams of more experienced climbers were also on the route, but behind us. I was nervous that I'd slow them down once we roped up and started to climb. The first two pitches were the crux of the route (i.e., the hardest parts) and I was trying not to get it into my head that the group behind me was just waiting for me to move forward. I struggled with both pitches, resting often on the rope to try and figure out the moves and burning my arms out quickly. The route was graded at a 5.8, much lower than what I can climb in an indoor gym. I was only able to get through the route once I relaxed and thought carefully about the movements and holds I needed to execute (and I also pulled on the protection once). After the first two pitches, the rest of the route was challenging and fun, but nothing that pushed me to my limit.

There were several run-out sections (i.e., the distance between the pieces of protection was far) where a fall would hurt quite a bit. I tried not to think about it and trusted my feet. All the climbing we were doing was also not in rock climbing shoes. We were wearing approach shoes the entire time, a hybrid of hiking boots and rock shoes, which made the footholds a bit sketchier.

I did walk away with some cuts from my first crack climbing experience (i.e., jamming my fingers and feet into a crack and twisting them to create a hold that I could move up on), but for the most part I tried to avoid crack climbing because it was a new technique for me. Instead, I tried to rely on laybacking which I was told was a lot more taxing on my body.

We named ourselves Team Unnatural Gas, after realizing how badly our frequent farts smelled. The three of us were guilty of this.

We didn't linger at the summit for too long. Unlike yesterday, the descent was a lot of fun. There were moments of careful downclimbing, walking along short and steep ridges, and two long rappells before we made our way off the spire.

We were back over an hour before the rest of the group, which surprised me. I assumed I would be the reason everyone was held back, but that may have been compensated for by the fact that Sam knew this route extremely well. Luke and Sam entertained themselves with a cherry pit spitting contest in the parking lot while we waited.

Back at camp, we made plans for the final objective, which would be student-led. Our goal was to summit Mt. Shuksan. I avoided the planning entirely, partly because I wasn't feeling very social and I also thought there were too many cooks in the kitchen. It had been over a week with the group, and I was used to spending a lot of time on my own back home. After dinner and a quick bath in the cold creek, I went to bed.

APPROACH TO MT. SHUKSAN

For the last objective, I decided to pack lightly, a choice I would later regret. Given how warm it was on Mt. Baker, I left my rain pants in the van. The forecast called for a low chance of precipitation, and that sounded like sunny skies in my book. Since this would be a student-led ascent, we had to learn how to pace and take breaks as a group, listening for and anticipating the needs of the team.

It took some searching to find our campsite, particularly because there was apparently a toilet that we could use. There was uncertainty about whether or not it was buried under snow, so a few of us split up to go searching.

Although I didn't use the famous toilet with a view overlooking Mt. Baker, I was glad we kept moving and settled on a very picturesque camspite.

The clouds in the distance signaled a storm was approaching tomorrow, on our summit push attempt. We made plans to rope up at 3AM only if there wasn't snow or rain falling on us.

Rather than focus our energy on rest, most of us ended up spending the next few hours taking photographs of each other and enjoying the sunset. Alejandra and Sarah even had a session of acroyoga.

Luke and I stayed up a little later to watch the entire sunset pan out. I admitted to him that I didn't really care if we made it to the summit or not. I had a fun time anyway, and I already knew I was more than capable of making it to the top of the mountain.

MT. SHUKSAN SUMMIT PUSH

There was neither snow nor rain when we woke up at 2AM, but the visibility may have been at about 100ft. It stayed that way for hours.

This was the whiteout that I was looking for earlier. It seemed like peering into the inside of a ping pong ball. I had to keep my sunglasses on to avoid the sunburn. In a thicker whiteout, it would be possible to sunburn the roof of your mouth from just breathing through your mouth.

After a few hours of moving slowly up the glacier, one of our teammates felt ill and we made the decision to turn around. This would be my turn to lead the team, and I was excited and feeling confident with each step I took. I could only clearly see a handful of footsteps ahead of me at any time, so my focus was entirely on finding the signs of the path that we took up. I'm not sure how I would have fared if the whiteout had been thicker.

We made it back to camp and rested for a few hours. It began to rain almost immediately after I stepped into my tent. I had a breakfast of M&M's that I packed two weeks ago and listened to music that I saved offline on my phone.

My nap was broken by the sound of Luke outside. I could hear the torrent of rain outside pounding the walls of my tent. The moisture outside had pooled up and soaked my sleeping bag, so I knew it was time to wake up. Luke was on the other rope team, which continued to move up the mountain. His rope team ascended despite the rain, but made the decision to turn back just 300 feet shy of the summit. At that point, their team was on the rock climbing portion of the route and wasn't feeling confident enough to move forward.

The heavy rain seemed to show no signs of letting up, so we made a plan to break camp within the hour and get off the mountain. At this point, both Luke and I were kicking ourselves for not bringing our rain pants.

Several of us were done packing early, and from our perspective it seemed as if the rest of the group wasn't moving fast enough. We made the decision to leave with one of the guides, hoping that the weather would be more agreeable at a lower elevation.

We ran down the mountain as fast as we could, and were at a great pace when Will said we needed to stop at a certain point under the cover of trees. He had promised Alejandra that we would wait for the second half of the group. I didn't like this plan. My pants hadn't gotten soaked yet until this point, when we stopped. I became restless and tried to convince Will that we could leave some a sign that indicated that we had moved forward. Will insisted on staying, so I did my best attempt to convince the other students to run down the mountain with me.

That became, for me, the most fun part of our chaotic descent. The top few inches of snow had turned to slush and we had extended runs of glissading (i.e., controlled sliding) on our backs and feet along the steep descents. There wasn't anyone else around, but they would've heard a lot of hooting and hollering on the mountain. After several miles of running downhill on snow, we finally saw a break in the clouds. My waterproof boots were full of water from my soaked pants dripping down my legs. I opted to take both off and run in my underwear and approach shoes. At this point, I was on a mission to leave the mountain and offered to help Janet by taking the wet (and now heavier) rope off her back. Luke, Janet and I made a manic push for several hours at a fast pace, assuming there was only a mile left when in fact there were several.

Once we got to the van, and the rest of the group caught up, Christian and I decided to split a hotel room instead of spend the night camping in our wet sleeping bags.

FINAL DAY

The last day of the course was intended to review any material we didn't get a chance to cover. I was barely paying attention. For me, the fun part was over, and I was exhausted mentally. There was no way I would remember any of it. I was ready to go home.

We said goodbye to each other and I thought about whether I'd see my new friends again on the trail anytime in the future. There was a lot we learned and experienced together, and a lot I learned from them as well. Several of them were in fact quite inspiring and gave me ideas on how I would want to spend my time in the outdoors. I also walked away with a lot more poop stories than I could have expected.

Big thanks to Alejandra Garces (@aj_pozo) and Will Nunez (@mountainspirations) for being good friends and mentors while keeping us all safe.

Also to American Alpine Institute (@alpineinstitute) for structuring such a comprehensive course in alpine mountaineering and technical leadership. There are four parts, and this was only the first section.

Very happy to have shared my first experience on a glaciated mountain with so many new friends. Certainly won't be my last mountain.

Looking forward to the next time I get to rope up.